Social values and tragic choices

The situation that Labour currently finds itself in, and in particular the choices it will face if it forms the next government, call for some uncomfortable thinking.

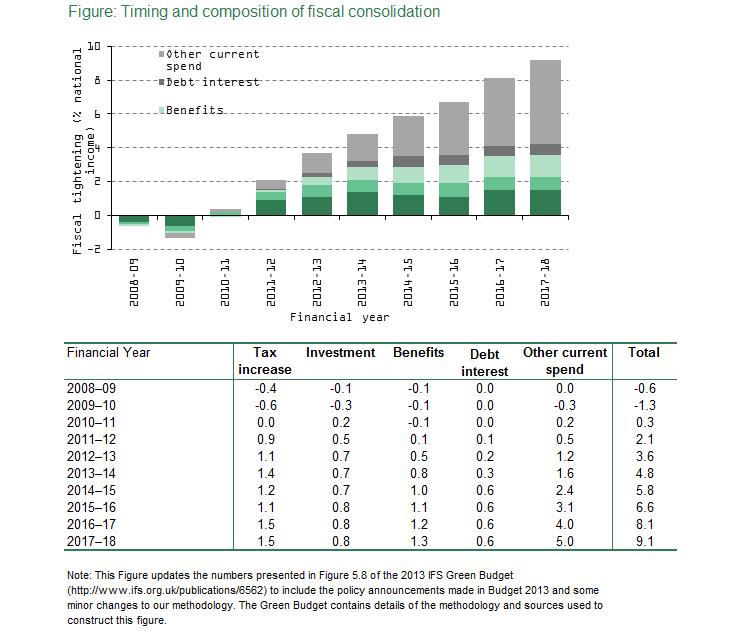

It is hard to imagine a plausible scenario in which a post-2015 Labour administration wouldn’t be faced with decisions where whatever options it chose the party’s fundamental values would be called into question. By then we will already have seen unprecedented cuts to public services and benefits- most of which, it it worth remembering, have not yet taken place (See chart & table from IFS. According to the IFS today http://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/6683, 58% of benefit cuts and under a third of cuts to services planned for the period 20010/11 to 2017/18 will have taken place by the end of this financial year). Even if further cuts or tax increases post-2015 were not necessary, and this is very unlikely if the next government wants to reduce the deficit even at a slower pace than the coalition, repairing any of the inherited damage to public services or the welfare system would mean moving resources from one already underfunded area to another. This is before even considering areas such as childcare and housing where many in Labour believe that expansion is sorely needed to support long-term objectives, or the continuing and increasing expenditure pressures associated with population ageing.

In other words, whatever decisions Labour makes if it wins in 2015, some of its choices will hurt people: and it won’t have the option the coalition has so ruthlessly exploited of pretending all the people being hurt deserve it.

This situation would have much in common with the account of tragedy given by the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre - who has some claim to being the most important intellectual influence on much of Labour’s current thinking: MacIntyre writes: ‘There are indeed crucial conflicts in which different virtues appear as making rival and incompatible claims upon us. But our situation is tragic in that we have to recognise the authority of both claims..... to choose does not exempt me from the authority of the claim which I choose to go against.’ (After Virtue, p. 143) This definition of the tragic situation seems a lot more relevant to Labour’s prospects than the sloganistic invocations of ‘virtue’,’tradition’ and ‘community’ that characterise some of the MacIntyrean strain in the party’s current debate.

Where some of Labour’s MacIntyre disciples are on the right track though is in recognising that our standard toolkit for thinking about policy is inadequate for the situation Labour would be faced with if it won the next election. Policy makers like to think of conflicting aims and values in terms of ’trade-offs’ at the margin: we’ll accept so much extra income inequality in return for so much extra tax revenue (we hope), in much the same way as we might trade an extra glass of wine off against increased risk of a hangover. But not all policy choices take this form even under favourable economic circumstances. When the options in play involve far from marginal choices, framing problems in terms of measured trade-offs may just be a form of wishful thinking. The range of options may be such that choices between values are forced on us. And if we are forced to choose between values, what is going to inform that choice?

This is not just a philosophical question. To take some concrete examples, there is a substantial risk that by 2015 there will be a crisis in social care provision in the wake of unprecedented cuts to local authority funding combined with growing demand from an ageing population http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2013/may/08/social-care-chiefs-fear-sy... . Many disabled and elderly people will be suffering increased social isolation and some will be receiving utterly inadequate help with basic personal care. There will also be a continuing rise in child poverty: in the IFS’s words, poverty will increase ‘in each and every year from 2010 to 2020’ primarily as a consequence of the coalition’s welfare changes http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2013/may/07/uk-children-poverty-2020-t... . We have reason to believe, not least from the historical evidence from the last major rise in poverty in the 1980’s, that increased poverty will have serious long-term consequences for a large minority of the children affected.

These two issues both go to the heart of Labour’s value system, and they are far from being the only examples. Labour will have to ‘recognise the authority of both claims’ and of many others: but it won’t be able to meet all of them even partially. Nor will it be ‘exempt from the authority’ of the claims it chooses to go against, unless it chooses to revise its values.

Under these circumstances, trading off is unlikely to be the main paradigm for decision-making. Nor are there obvious alternatives. Running through some examples from the political philosophy literature, a minimax decision rule – minimise the maximum loss suffered as a result of cuts– might seem appealing but it would need a single currency which can be applied to different priorities in order to bite: for example, a way of comparing the consequences of inadequate social care and increased child poverty. The obvious candidate for deriving a single currency is utilitarianism, simultaneously the most derided serious theory in ethics and the most practically indispensable for public policy. But, notoriously, utilitarianism won’t resolve conflicts involving values other than utility, such as individual autonomy and social cohesion. Alternative currencies such as ‘capabilities’ which aim to bring other values into play offer only the broadest guidance, unsuited to the precise decisions that will need to be made.

One way of managing conflicts between values is to appeal to an overarching principle which can somehow adjudicate between different value claims. But even if one thinks of social democracy or liberal egalitarianism (or republicanism or communitarianism etc) as reasonably coherent political doctrines, the notion that they have /that/ kind of coherence (‘all the way down’, as they say) looks implausible. And the timetable for arriving at the sort of public ‘reflective equilibrium’ on balancing different values advocated by John Rawls is, to put it mildly, unforgiving, even if you think that ‘reflective equilibrium’ is a remotely plausible outcome of what passes for debate on spending choices in the UK these days.

Would all this leave Labour bereft of principles to address the choices it will face if it wins in 2015? Of course not. There will still be choices where principles of urgency and priority will offer clear guidance- as is recognised even in some of the coalition’s policies- although implementing those principles always carries risks. Policies that aim to help only the most vulnerable inevitably leave many of the most vulnerable unhelped, a key argument for the sort of broadly based provision social democrats have always favoured. And of course not all decisions will be about expenditure: reversing the NHS Act, banking reform and – arguably- active labour market policy and labour regulation will be important to long-term social welfare, although they are unlikely to completely offset the effects of retrenchment in social infrastructure.

But if Labour wins I can’t help thinking there will be tragic choices, in MacIntyre’s sense, as well. This is not (quite) a counsel of despair. It’s central to MacIntyre’s notion of a tragic situation that there are better and worse ways to proceed even when every option inevitably involves going against a claim with an authority we recognise. That’s what makes a situation tragic rather than merely deplorable. But recognising that there are choices is cold comfort indeed. We are still faced with the question: what guides choice under these circumstances?

Here is one suggestion, borrowing some terminology from the political economist Peter Hall who distinguishes between policy ‘instruments’ (such as taxes, benefits and public services) and the ‘settings’ of instruments, such as tax rates. Some of the damage to be repaired post-2015 may well be structural, affecting the availability of ‘instruments’, for example, if social care reaches a point of crisis. Some will certainly be to do with the ‘settings’ of instruments (such as benefit rates, affecting poverty). Repairing the former might be seen as taking priority, as the loss of important ‘instruments’ may eventually become irreparable, while as long as ‘instruments’ haven’t been reduced to near-ineffectiveness, ‘settings’ could be adjusted as economic and fiscal circumstances improve, as one hopes they eventually will.

Even if prioritising structural repair provided some guidance on policy choices, it wouldn’t reduce the authority of the claims which have been given lower priority: we remain within the tragic situation. The argument outlined here for prioritising structural repair does not turn on saying that one value is more important than another but on the ‘path-dependency’ of future policy choices, for example if failing to address the shortfall in social care as a matter of urgency locks provision into long-term decline as those who are able to come increasingly to rely on outside options- private provision, charity or families- leaving public provision patchy, arbitrary and inadequate.

There is of course another way of dealing with tragic choices: if you face incompatible claims which are equally grounded in values you hold important, there is the option of revising your values. I’ll return to this option in a later post.