Retrenchment, reform, continuity: welfare under the coalition

Under continuity, the coalition’s decision to proceed with the previous government’s planned reassessment of incapacity benefit claims was a notable policy mistake which led to the near-collapse of the assessment system by 2014. Retrenchment measures are dominated by benefit uprating changes which, along with measures targeting higher-income groups, have been less regressive than alternative approaches to expenditure reduction. However these changes were accompanied by a number of smaller scale retrenchment measures, the cumulative impact of which have involved substantial concentrated negative impacts. Retrenchment has thus been less regressive than it might have been but more regressive than it needed to be, taking the retrenchment targets as given. Policy failure and exogenous economic factors have offset the effect of retrenchment measures, with the result that expenditure by 2014/15 was little different to that planned in the Labour government’s last budget. Full implementation of major reforms has been deferred to the next parliament. The main achieved policy change has been an unprecedented tightening of the benefit sanctions regime.

A slightly different version of this article appears in the February 2015 National Institute Economic Review http://ner.sagepub.com/content/231/1/R44.abstract (£).

Introduction

The coalition government that came to power in May 2010 was committed both to a major programme of fiscal retrenchment and deep reform of the working age social security system. It also inherited a number of planned social security reforms from the previous Labour administration which it decided to implement in whole or in part. By any standard 2010-2015 has been a period of intense policy activism in welfare. With what results? This note gives a broad (and inevitably provisional) overview of policy change under the coalition.

There has been a lot of welfare policy: in order to impose some order on this complex field we group policy development under the themes of ‘continuity’, ‘retrenchment’ and ‘reform’. Under ‘continuity’ we group policies originating under the previous government. By retrenchment we mean measures which aim to reduce expenditure while remaining within the broad parameters of the inherited system; by reform, we mean large scale redesign of benefits. These distinctions should be seen as rough and ready: deciding which side of the line between retrenchment and reform a policy falls for example is often a matter of judgment. The approach here is to distinguish retrenchment from reform according to what is involved in implementing the policy in question (adjustment or wholesale change) rather than its overt or imputed rationale or their planned expenditure impact. 1

Welfare retrenchment has been controversial not only because of the impact it is claimed to have had on individuals but because it serves an overarching policy aim which is itself controversial – fiscal consolidation on a timetable adopted in 2010 which was regarded by many as too rapid (and was later modified by the coalition). In this piece, we ignore this issue, in effect taking the coalition’s deficit reduction objectives as given, which should not be read as a comment one way or another on those objectives. We also take as given the split between tax rises and spending cuts in cutting the deficit , the protection of certain budgets and the decision to protect and even increase state pensions and pension credit, inevitably increasing the burden of retrenchment on working age benefits.

We begin by looking at some key aspects of the social security system the coalition inherited in 2010; sections 2-4 look in sequence at continuity, retrenchment and reform measures and section 5 concludes.

1 The inherited system

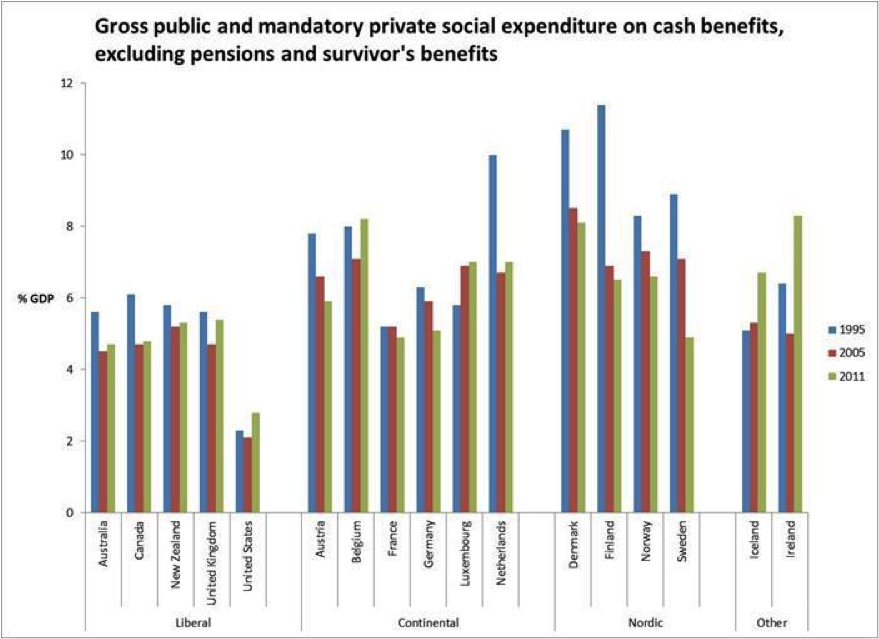

Although it is often asserted (not least by coalition ministers) that welfare spending was on an unsustainable upward trajectory prior to the 2008 crash, overall expenditure, whether for all age groups or just those of working age, had shown little structural change over recent decades. As the Office for Budgetary Responsibility note in their first Welfare Trends report ‘Over the past 30 years....the proportion of national income devoted to welfare spending has not shown a significant upward or downward trend over time’ 2. It is also useful to compare internationally: figure 1 shows working age cash benefit spending (for 1995, 2005 and 2011) for 17 comparably wealthy nations grouped using a standard typology of welfare states 3. This shows that expenditure as a share of GDP in the UK is similar to that in other members of the relatively low spending ‘liberal’ group (with the exception of the extreme outlier that is the United States), and that this has been the case for a long time. Neither historical nor international comparison support the view that the benefit system inherited by the coalition involved exceptionally high expenditure.

The relatively low expenditure of ‘liberal’ welfare states is largely explained by the lower prevalence of earnings-related benefits, which particularly affects spending on unemployment and sickness/disability benefits. In contrast, expenditure on family benefits (such as child benefit and child tax credit in the UK) in liberal regimes including the UK is not generally low by rich-nation standards (again with the exception of the US) 4.

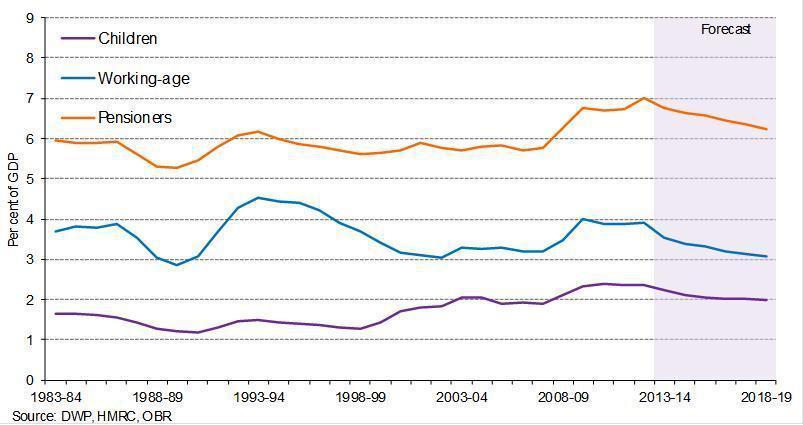

The family focus in the UK benefits system has become more marked over time, as can be seen in figure 2: indeed the expansion of benefits for children (mainly through tax credits) was one of the most striking developments in benefit spending under the Labour administrations. Given the tendency for welfare policy in the UK to be viewed solely through prism of worklessness, it is worth noting that the growth of tax credits from the late 90s was mainly driven by awards to working families.

Given the stability in overall working age expenditure, the counterpart to increased expenditure on family benefits from the late 90s was a major reduction in spending on the main out of work benefits, reflecting generally benign labour market conditions and policy interventions as well as the general downward impact on spending as a share of GDP of uprating benefits with prices rather than earnings. (Benefit entitlements for the unemployed without children in the UK are exceptionally low, even compared to other countries with flat-rate unemployment benefits 5.) Unemployment fell to its lowest levels since the 1970s prior to the 2008/9 recession, and even then rose far less than had been anticipated. Employment for single parents, which fell from 60% to 44% between 1980 and 1995, increased steadily from the mid-90s, even during the extended labour market downturn from 2009 to 2012, and now stands at the highest level on record. Incapacity benefit caseloads were the exception to the strong downward trend for out of work benefit receipt, although they did fall to some extent from the middle of the last decade and the apparent stability of the caseload disguised contrasting underlying trends- sharp falls in receipt among older men, increased entitlement for women and higher rates of receipt among younger age bands, mainly associated with mental health problems (the latter a trend shared with many other welfare states over recent decades 6). However expenditure on incapacity benefits had been on a sharp downward trajectory since the mid 1990s 7, as tighter contributions conditions increased the extent of means-testing.

Two parameters of the tax and benefit system which are important in the context of welfare reform are the participation tax rate (PTR- the percentage of gross earnings lost to direct tax and benefit withdrawal on moving into work) which in theory affects incentives to work at all, and the effective marginal tax rate (EMTR - the marginal tax rate taking account of benefit withdrawal) which affects incentives to increase earnings when in employment. At low wage levels, PTRs of 60% and over, particularly for families with children, are common in wealthy nation welfare states: the UK is not exceptional in this respect 8. EMTRs for low wage workers are however high by international standards, and high marginal rates extend further up the earnings distribution. Confusion between these two parameters is endemic in popular welfare debate, including around the coalition’s Universal Credit reform.

2 Continuity

The coalition inherited a number of planned policy changes from the previous government, including changes to the state pension age, new worksearch requirements for single parents and reassessment of benefit entitlement for incapacity benefit claimants. Of course no government can bind its successors and the coalition could have chosen to abandon or change any of these plans. In the event it accelerated the rate at which the state pension age would increase 9, modified plans to impose worksearch requirement on lone parents with younger children and decided to proceed with the reassessment of IB claimants.

The imposition of worksearch requirements on single parents was an innovation of Labour’s last term in government, with conditionality introduced initially for parents of children over 12 and later over seven, with the intention of further lowering the youngest child age threshold to three. Evaluation of the earlier stages of imposing conditionality has shown positive impacts on employment rates (although also some evidence of parents disappearing- neither in receipt of benefits nor working) 10. Initially, the coalition reduced the age of youngest child at which conditionality applied to five rather than three: however, subsequent changes effectively mean that parents of three and four year olds can be brought within the conditionality regime 11. These decisions passed off without major controversy.

The decision to reassess the great majority of IB claimants on the other hand proved to be a major error, leading eventually to the collapse of the assessment system for out of work sickness and disability benefits in 2013/14. The background lay in Labour’s 2008 replacement of IB with a new benefit, Employment Support Allowance (ESA), which had a tougher assessment of work potential (the WCA) and which divided the caseload into an unconditional ‘support group’ for people not expected to be able to work again and a group which, while not at present fit for work, was subject to some conditionality in terms of ‘work-related activity’. Although these changes were expected to reduce flows on to the benefit and increase flows off, gradually reducing numbers of claimants, the main impact on the caseload was expected to come from reassessment of existing IB claimants, which was expected to lead to large numbers of claims being rejected. The French company Atos Healthcare was appointed to carry out the assessments. Reassessment was to be piloted in a number of areas starting in 2010 before national roll-out. Warning signs about the assessment of new claims quickly appeared in the form of a high rate (40%) of successful appeals against WCA decisions.

The original legislation had made provision for an annual review of the operation of the WCA for five years from its introduction. The report of the first independent reviewer, Sir Malcolm Harrington, in November 2010, was critical of the assessment process, particularly with regard to how it dealt with mental health problems and fluctuating health conditions, and recommended a number of changes, some of which were eventually implemented. It was later revealed that Harrington had advised against proceeding with the roll-out of reassessment, scheduled to begin in the spring of 2011, until the problems identified had been addressed12.

Reassessment made the existing concerns about the assessment process a national issue, with the annual number of successful appeals against WCA decisions increasing more than sevenfold between 2009/10 and 2013/14, from 19,000 to 136,000. By the second quarter of 2014/15, some 366,000 appeals against ESA decisions had been upheld since 2010/1113. At the same time the assessment system and the provider were plainly overstretched: reassessing the existing caseload meant that the volume of assessments to be carried out by Atos doubled at the same time as implementation of Harrington’s recommendations was slowing down the assessment process. By June 2014 a backlog of 700,000 claims awaiting assessment had built up. Volatility in the outcomes from the WCA further undermined its credibility: the percentage of reassessed claims found fit for work fell from 30% in February 2011 to 10% by August 2013. In March 2014 Atos, by now a household name for all the wrong reasons, resigned the contract for delivering the WCA.

In the second edition of their The Blunders of our Governments King and Crewe consider what they describe as the ‘horrendous failure’ of ESA assessment primarily as an example of flawed outsourcing14. The case certainly raises questions about government’s expertise in contracting and the competence of providers- questions that will continue to arise not only for the WCA but for the new assessment for Personal Independence Payment . But why did DWP not heed Harrington’s advice to delay reassessment until the system had been improved? The context of retrenchment cannot be ignored. In March 2011 (thus, just before the national rollout of reassessment) DWP was forecasting that expenditure on incapacity benefits would fall from £13.2 bn to £10bn (nominal) by 2014/15: it is all too easy to see why a department which was already tasked with delivering major expenditure cuts would have been unwilling to sacrifice these savings. In the event, expenditure in 2014/15 is now forecast to be £3.7 bn higher than forecast in 2011.

3 Retrenchment

By the end of the current parliament policy decisions on working age social security and tax credits will have amounted to about £18bn of net spending reductions in nominal terms: in other words, other things being equal, expenditure in 2014/15 would have been this much lower against the baseline of inherited planned spending had all of these policies been successfully implemented15.

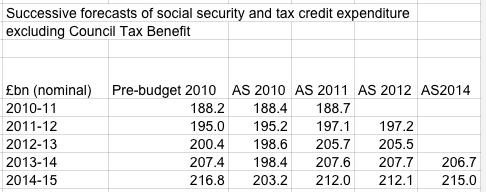

The actual path of expenditure is a different matter. At the time of the 2010 Autumn Statement, the OBR forecast implied a nominal reduction of 13.6bn in welfare spending against the baseline of Labour’s March budget. Outturn expenditure proved higher than expected and a further round of cuts was introduced in the 2012 Autumn Statement- in other words ,the coalition was cutting more in order to get back to plan. Even so, on the OBR’s current forecast, only about half of the originally planned reduction will have occurred by the end of 2014/15. Even this is something of an overstatement, as about £4.8 bn expenditure on Council Tax Benefit (CTB) was removed from social security spending and devolved to local authorities from 2013/14. On a like for like comparison excluding CTB (see figure 3), Labour’s spending plans for 2014/15 were for £216.8 bn, compared to the current forecast of £215 bn. It is thus not clear that there has been any substantial reduction against the baseline. (Of course, Labour would almost certainly have modified its plans had it won the election.)

There is not scope here for a detailed account of where the axe fell, but it is useful to look at the composition of planned cuts in broad terms. Planned expenditure reduction was mainly driven by retrenchment measures in the sense outlined above, with only one ‘reform’ measure making a major contribution ( the disputable case of DLA reform- see below). In all nearly £12 bn of the planned £18bn total retrenchment comes from uprating policy decisions (including below inflation uprating and freezes for some benefits as well as moving from RPI to CPI as the default basis for uprating), one of the effects being to spread the pain of cuts relatively widely and thinly17. Restricting child benefit for higher earners reduced spending by an estimated £2.7 bn; higher earners were also targeted by cuts to the quasi-universal ‘family’ element of child tax credit.

The other major retrenchment measures specifically concerned housing benefit and Employment Support Allowance. The eligible rent for housing benefit entitlement in the private rented sector was reduced from the median to the 30th percentile of the local rent distribution, and single claimants up to the age of 35 were restricted to single room rents. Contributory (as opposed to means-tested) ESA was time limited to one year. While these retrenchment measures yielded substantial savings, there was also a host of smaller scale measures which taken individually made little contribution to deficit reduction, some of which were to prove particularly controversial.

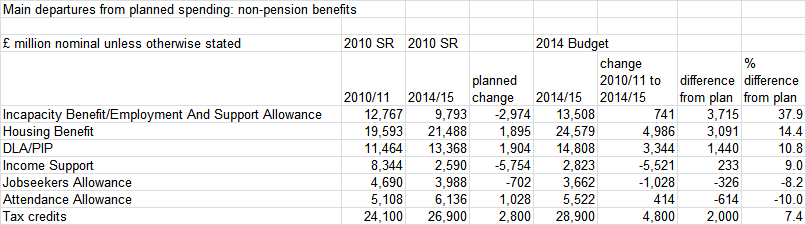

Why did expenditure turn out so much higher than forecast? The reasons are split between policy /forecast error and exogenous economic factors in roughly equal measure. Figure 4 shows the benefits which departed siginificantly from plan. The ESA fiasco led to an extra £3.7bn in 2014/15. The decision to defer the planned rollout of PIP (the replacement for DLA- see below) cost a further £1.4bn. Higher than forecast expenditure on housing benefit and tax credits is explained by economic factors – most importantly, an unprecedented stagnation of nominal wages.

What about the distributional consequences? It is virtually impossible to make major cuts to working age social security spending in the UK without regressive consequences, as the system is highly progressive. However policy choices affect the level of regressivity. We have seen that the bulk of cuts arose from either changes to uprating or measures targeting higher earners. Given the scale of planned retrenchment (and the protection of pensioners’ benefits) these are perhaps the least regressive measures available.

The most recent (at time of writing) study of distributional impacts17 indicates that benefit cuts were widely distributed across the lower half of the income distribution18. Benefit losses amounting to between two and three per cent of (equivalised household disposable) income are registered across the bottom 55% of the population, with only the bottom 5% showing substantially greater losses (about 4.5% of income)19. However changes to taxes and pensions offset these losses to a varying extent according to income. The result is that even in the bottom half of the income distribution overall losses reduce with rising incomes, and from the middle to just below the very top of the distribution income changes become positive. Thus the combined effect of working age benefit cuts, pension increases and tax changes meant that the middle and most of the upper range of the income distribution were protected from retrenchment. Arithmetically, it is clear that other distributional outcomes were achievable within the same fiscal envelope: indeed, the analysis cited here concludes that the overall effect of tax and benefit changes taken together was fiscally neutral.

If welfare retrenchment taken on its own mainly took this (in relative terms) moderately regressive form, are concerns about the impact of austerity misplaced20? Such an inference would not be justified: the measures with the biggest impacts on spending are not necessarily those with the biggest impacts on individual households. Some measures – whether ‘reform’ or ‘retrenchment’ in our terms - which yield little in terms of fiscal savings are likely to impact heavily on specific groups of claimants: some households will be affected by more than one of these measures. A weakness in most assessment of distributional impacts is that by averaging even over quite narrow ranges of the income distribution they fail to capture the cumulative, concentrated impacts of specific measures. As scoping research for the Equality and Human Rights Commission has shown, these cumulative impacts can be both substantial and widespread21.

A safer provisional conclusion would be that while the coalitions' most effective retrenchment measures have been mildly regressive taken on their own, it has also undertaken a lot of smaller scale retrenchment measures - such as the so-called 'bedroom tax', abolition of the social fund and cuts to Council Tax Benefit - which have impacted more heavily on some groups, including single parents and disabled people. The combined fiscal impact of the latter type of measure is not large in the context of overall welfare spending or deficit reduction targets. The harshest impacts of retrenchment have resulted from the least effective retrenchment measures.

Finally it is important to note that distributional assessments do not generally take account of variation in inflation rates across the income distribution. Recent ONS research22 confirms that over recent years, lower income groups have faced considerably higher inflation. Given the fiscal impact of uprating policy changes, it seems likely that a distributional assessment with adjustment for differential inflation would show a more regressive pattern for housheholds in lower income deciles.

4 Reform

[I]f welfare reform is to be successful, the merits of different systems must be understood, especially the merits of the system which is to be replaced. Akerlof, G. 23

The coalition's reform agenda can be divided into four main areas. Awkwardly perched on the dividing line between retrenchment and reform is the abolition of Disability Living Allowance (DLA) and its replacement by Personal Independence Payment (PIP). A series of 'caps' have been applied both to individual benefit entitlements and overall expenditure. Universal Credit promises to reshape large swathes of the working age benefit system. Finally it is necessary to consider operational changes to the benefit system, in particular sanctions policy.

The abolition of DLA, which compensates for the additional costs of disability, is intended to lead to a 20% reduction in the working age caseload and expenditure. The scale of the change means this counts as a 'reform' in our terms, but the motivation is clearly retrenchment (the policy, including estimated savings, was announced without preparatory policy work by the Chancellor in the 2010 ‘emergency’ budget). DLA expenditure has indeed been growing over time, but the policy change will only immediately affect people of working age, who account for a little under half of expenditure growth24. The echoes of ESA policy are worrying, with reassessment of existing claims against tighter criteria expected to yield the bulk of savings, and with the new assessment system developing large scale backlogs even before reassessment began: reassessment has now been deferred to the next parliament.

The introduction of 'caps' must be seen as largely rhetorical. The decision to cap total family entitlements at £26,000 was justified on the grounds that benefit claimants should not receive more than average earnings, a rationale turning on a deceptive comparison of income (benefits for claimants) with one component of income (earnings for workers) ignoring entitlements to in-work benefits. (The myth that people are better off on benefits than in work is one which the coalition has not only failed to challenge but has actively promoted.) The imposition of an overall cap on 'welfare' spending was widely, and in our view correctly, seen as a purely political manoeuvre intended to embarrass the opposition, following, it must be said, the example of Labour's 2009 Child Poverty Act, intended to embarrass the Conservatives -and with about as much likely impact on any major future policy decisions.

The coalition’s major reform was Universal Credit, a comprehensive reshaping of working age social security and tax credits. At the centre of the reform was the simplification of entitlements, conditions and benefit withdrawal rates, combining tax credits, out of work benefits and housing benefit into a single payment with a single withdrawal rate over different earnings levels. As the administration of these benefits was split between two government departments and local authorities, the route to 'simplification' was far from simple.

The idea of combining existing benefits was not new. Indeed the idea was not new to the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions Iain Duncan Smith, who had proposed what later became Universal Credit as long ago as 199425. Reforms in Labour’s last term had already opened up the possibility of combining Income Support, Jobseeker’s allowance and work-related Employment Support Allowance into a single benefit26 (Freud 2007; DWP 2008). Risks had also been noted, reflected in the note of caution sounded in the Gregg review on benefit conditionality in 2008: ’Change would have to be delivered over many years and carefully monitored’. (Gregg 2008 pp.)

Nonetheless if there was continuity with previous policy thinking in the Universal Credit proposal, it went far beyond previous proposals by seeking to bring tax credits and housing benefit within the single benefit and merging administration with the tax and National Insurance systems in order to allow entitlements to be updated in 'real time'. These extensions threatened to bring the already recognised administrative and technological challenges of benefit simplification to a quite different level. The risks were amplified by DWP's decision to adopt an 'all or nothing' implementation plan under which all the pieces of the UC jigsaw - policy, administration and information technology- needed to come together simultaneously, an approach which contrasts not only with Gregg's warning but with the original staged reform proposal developed by the Centre for Social Justice (CSJ) thinktank prior to the election in 200927.

The rationale for extending the scope of benefit simplification lay in an argument about work incentives. The CSJ's original report stated ‘Our benefits system is broken. Although it alleviates financial hardship, it does so at a price. High benefit withdrawal rates trap millions in worklessness and dependency, often over several generations.....for those in low-earning jobs (60% of median wage or less) their [Participation Tax Rate] is almost always higher than the average for other European countries.’28

Read as a diagnosis rather than a political statement, this raises a number of problems. It glosses over major reductions in out of work benefit caseloads over the previous 15 years and it frames reform in terms of a virtually non-existent phenomenon, the mythological underclass of inter-generationally workless families.29 More seriously, there is either confusion or sleight of hand in the evocation of benefit withdrawal rates as the global explanation for ‘worklessness’. In the inherited system, the sort of high participation tax rates evoked in the report applied only to earnings from employment at low household work intensity (for example, less than 16 hours a week for a single parent). High PTRs in these cases were a policy choice, intended to prevent the benefit system subsidising low intensity employment. To present this policy choice as equivalent to trapping ‘millions in worklessness’ was patently ludicrous.

Unsurprisingly, then, the main impact of UC on the incentive to work at all is confined to hours of work which policy had previously aimed to avoid incentivising. To the extent that this encourages work among people for whom the only relevant choice is between low intensity work and worklessness (for example, some disabled people), this may represent a desirable change. However it is not clear why wholesale reform rather than targeted flexibility in hours rules is called for to achieve this end. An obvious risk arising from an untargeted approach is that some who would otherwise work at higher intensity will have incentives to shift to lower intensity, at a cost to the taxpayer. A further risk is that faced with a new supply of highly flexible labour, some employers will respond by reducing average hours in some types of job, so that some employees find their work intensity reduced involuntarily. Offsetting these new incentives is an original feature of coalition welfare policy: extending conditionality and sanctions to working households, with the government effectively directing lower income households as to how much they should be earning. This is new territory for social security, with no obvious precedents in other systems. DWP estimates that a million working age households will be affected but is rather vague as to what form the conditionality will take.23

Apart from reducing participation tax rates for part-time and marginal employment the effect of UC on work incentives is mixed: marginal effective tax rates rise for some groups and fall for others.31 UC, as originally intended, benefits one earner couples with children on average both distributionally and in terms of a reduced participation tax rate. However given the already low rate of household worklessness for couples with children (4.5% in 2013) this increased incentive to have at least one adult in work is unlikely to have any significant employment impact. UC substantially increases participation tax rates on average for both lone parents and potential second earners in couple families with children, but reduces the effective marginal tax rate faced by lone parents on average.

Given these diverse effects, and the decision to focus on improving incentives for the households with the highest employment rates (couples with children) it is not surprising that the employment benefits of Universal Credit are thin: £7bn (in cash terms) over a 12 year horizon, or about £600m a year, most of which takes the form of savings for government rather than increased disposable income for households.32

UC implementation is at time of writing well behind schedule with questions over whether the IT problems which have bedevilled it are in fact resolvable. This threatens the entire future of the programme, as its all-or-nothing implementation plan means that without all pieces of the puzzle being in place, the costs of partial implementation (using manual processing of claims) is prohibitive. As we approach the end of this parliament, UC is far from being a fait accompli.

Although Universal Credit has cross-party political support, it is far from clear what that support is based on or how deep it runs. Agreeing with ‘the principle of UC’ seems to mean no more than agreeing that work should pay more than being on benefits, which is hardly an argument for replacing a system in which non-marginal work already pays more than benefits (however much the coalition has tried to suggest the opposite). The prospect of much more rapid adjustment of entitlements to changes in circumstances is attractive, but is dependent on as yet unproven improvements in IT. Marginal effective tax rates, which reduce the gain from working more hours or increasing earnings, will continue to be high and will rise for many due to the single taper rate. Conditionality will be relied on to achieve outcomes which are arguably better pursued through economic incentives, and as conditionality is itself costly, it may well not be up to the task. The superficially attractive idea of a single taper rate for all benefits ignores the fact that there are good, if debatable, arguments for people in different circumstances facing different withdrawal schedules, not least the fact that this makes it easier to provide more generous safety net benefits33. The root-and-branch recasting of the entire working age benefit system for the sake of gains changes achievable by other means looks like radicalism for the sake of radicalism.

Finally, the coalition reformed the operational side of the system, replacing Labour's Flexible New Deal of privately provided employment support with a Work Programme which shared most of its features; and greatly strengthening sanctions policy- both in terms of the severity of sanctions and the opportunities for falling foul of the conditionality regime. Sanctions now affect 6% of the JA caseload at a point in time, the highest share on record, and increasingly affect ESA claimants (who, it should be noted, have been found not to be currently fit for work), with the number of sanctions rising from 2,200 in the first quarter of 2012 to 15,900 in the first quarter of 2014.34 The rationale for this remains unclear: as one respected organisation in the field of employment services put it 'Over the last two years, we have seen an unprecedented increase in the use of sanctions and an inexplicable increase in their severity.' Retrenchment provides no explanation: although the numbers sanctioned are large, the savings are counted in the tens rather hundreds of millions35.

The balance sheet on reform at the end of the 2010-15 parliament is weak, although in the longer run the coalition’s record on welfare reform is going to turn on a decision to be taken by the next government- whether to proceed with UC. At this stage the record of achievement consists mainly of rhetorical policy initiatives and the introduction of a much harsher sanctions regime. Arguably, the coalition tried to do too much in one parliament in combining its own major reforms with an ambitious programme of welfare retrenchment and the continuation of the previous government's ESA programme.

5 Conclusion

Continuity with the policies of the previous government, major fiscal retrenchment and major reform are all part of the story of working age welfare under the coalition. However reform has been a minor strand in the narrative, with all of the most difficult aspects of implementation deferred to the next parliament.

Continuity has involved both the relatively uncontroversial extension of conditionality for single parents and the disaster of ESA reassessment. The latter, one of the major failures of welfare policy of recent decades, is ultimately the coalition's responsibility but its seeds were sown long before the 2010 election.

Claims for the effectiveness of reform have been made by the government and some of its media supporters36. based largely on employment performance since 2012. Given that there has been little reform (in our sense) we can hardly agree! It is true that retrenchment measures may have improved work incentives to some extent 37 by ensuring benefits did not rise faster than stagnating wages. However employment and unemployment since the crash need to be seen in the context of longer term developments in labour supply. Both unemployment and economic inactivity increased less with the onset of recession in 2008 than might have been expected from earlier recessions. Relevant factors include the closing off of various routes into economic inactivity through reforms under the Major and New Labour governments, rises in state pension age, the long term decline in the value of out of work benefits (replacement ratios in the UK were among the lowest in the OECD long before 2010) and- although this remains to be established- the greatly increased value of in-work benefits 38. The fact that deindustrialisation of employment had more or less run its course in the UK long before the 2008/9 crisis also probably mitigated the labour market impact of recession.

Retrenchment has not been as regressive as it might have been, but has arguably been more regressive than it needed to be (accepting the coalition’s approach to fiscal consolidation). The rush to cut in 2010-2012 seems to have facilitated bad decisions which will save little or no money while causing concentrated hardship: the 'bedroom tax 'and IB reassessment, the latter a case of a continuity policy which, in a less fraught fiscal climate, might have been deferred.

The next government will be faced with decisions on Universal Credit – whether or not to proceed - and on how to avoid the reassessment of DLA claimants turning into a repeat of the WCA disaster of 2011-2014. There will be fewer options available to make retrenchment less regressive, especially if pensioner benefits continue to be protected, and the consequences of continued below-inflation uprating would be highly regressive. The next government will also be faced with continuing problems which retrenchment policy has failed to contain: housing benefit costs for working families in the private rented sector and the cost of in-work tax credits. Thus welfare reform, in a different form to that envisaged by the coalition, may well be on the agenda for the next parliament.