Fog in channel: what do EU-27 nations think about freedom of movement?

It is sometimes asserted, in the context of Brexit, that freedom of movement of EU citizens is a source of public discontent not just in the UK but in other European nations. This claim seems to be particularly popular among advocates of a so-called 'soft' Brexit: for example, Alan Johnson (Labour) and Anna Soubry (Conservative but Brexit-sceptical) both made it on Radio 4’s Any Questions on 6 January,while Phil Collins asserted in the Times ‘the impeccable logic of allowing labour to follow where capital flows is not appreciated by the native populations of the host countries.’

In contrast, the received wisdom among UK Europe-watchers is that widespread discontent with freedom of movement is a UK (more precisely, English and Welsh) idiosyncrasy. Other EU nations are indeed worried about migration and cross-border movement, but the migration of EU nationals is generally seen as positive or neutral: it is migration from outside the EU, and the operation of the Schengen travel area (to which the UK does not belong), that are the sources of concern.

It is all too easy to see why the idea that freedom of movement is unpopular in other EU countries might be attractive to people worried about the prospect of a 'hard' Brexit. We are constantly told that the referendum result was a negative judgment on migration from EU countries. A Brexit deal exempting the UK from freedom of movement while allowing it to retain the privileges of single market membership is clearly a chimera. But if freedom of movement were as unpopular elsewhere in Europe as it seems to be in the UK, then maybe the EU would be willing to consider the sort of reform that might change the terms of the Brexit negotiations, even to the point of making it possible for the UK to remain within the EU or at least the single market.

So who is right? One way of getting an angle on this is to look at data from Standard Eurobarometer , the European Commission’s twice-yearly survey of public opinion in EU countries, which has been asking a battery of questions on attitudes to freedom of movement over recent years. These include questions on subjective feelings (positive/negative) about immigration of both EU and non-EU nationals, and on views on whether the right of EU citizens to live and work in (a) any EU country and (b) one's own country is good, bad or indifferent. Fieldwork for the surveys usually takes place in May and November, which is fortuitously useful for looking at UK attitudes pre- and post- referendum. This turns out to be important.

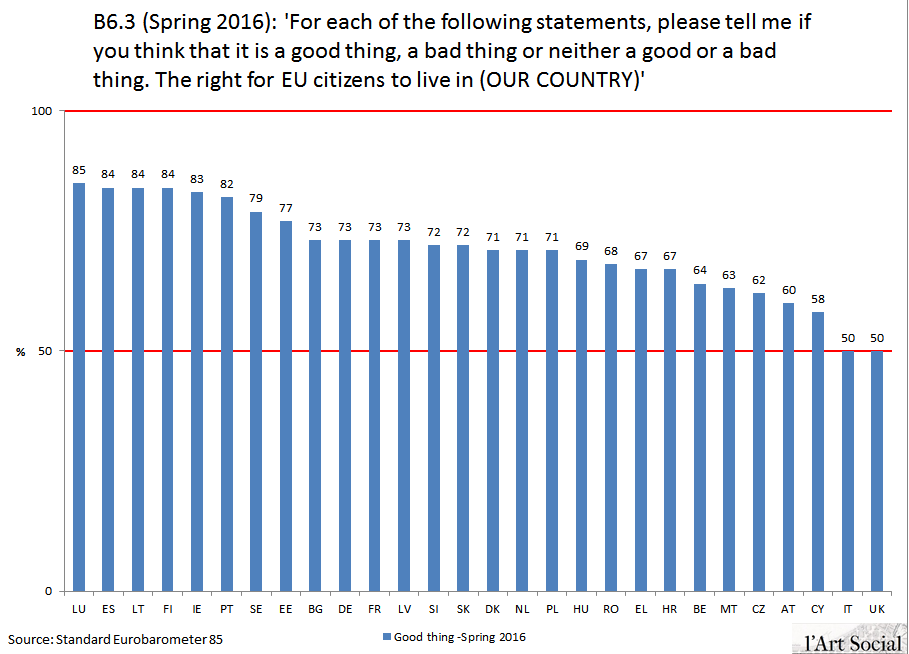

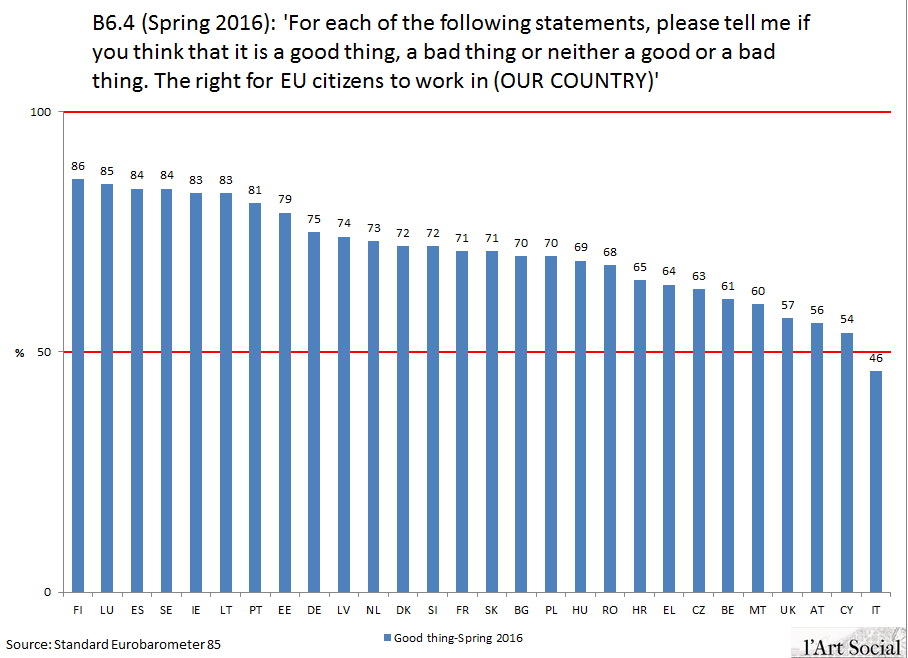

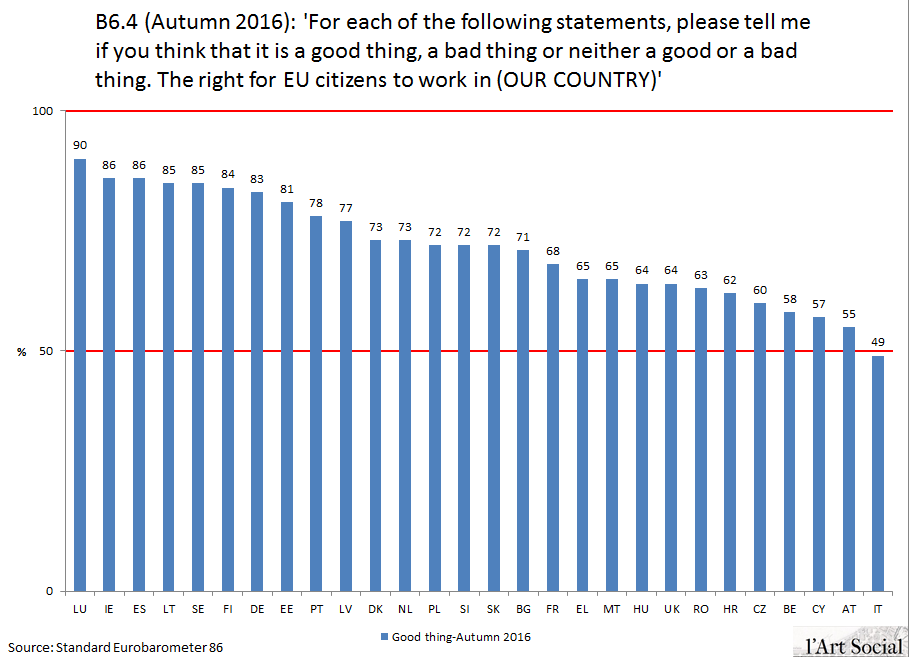

Charts 1 to 6 show the 'positive' responses to three of the Eurobarometer questions for both the spring and autumn surveys. The chart titles give the survey question number and wording. Chart 1, for spring 2016, might be seen as exemplifying what I've called the received wisdom about the idiosyncrasy of UK views. Majorities in almost all countries say that the right of EU citizens to live in their country is a 'good thing', ranging from over 80% (e.g. Ireland) to around 60% (e.g. Austria). The UK and Italy are the only countries where this view does not have majority support. So while the UK is not a statistical outlier on this measure, it is certainly at the extreme of the range. When it comes to views on the right of EU citizens to work in one's own country (Chart 2) the UK is substantially more positive (57%) and is very similar to Austria, although still ranked fourth from the bottom. There is little support for the idea of a general disenchantment with freedom of movement in the EU here.

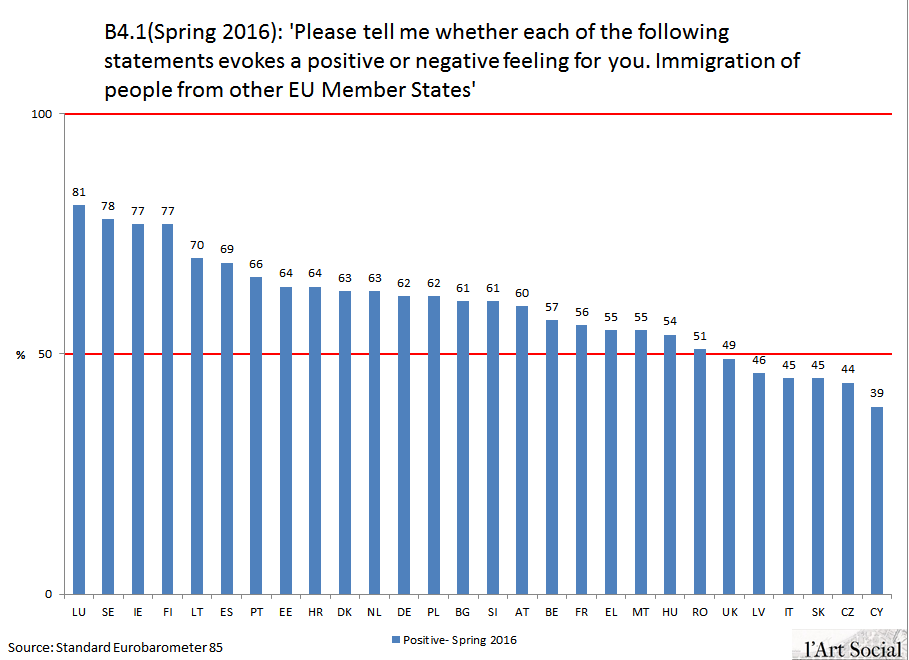

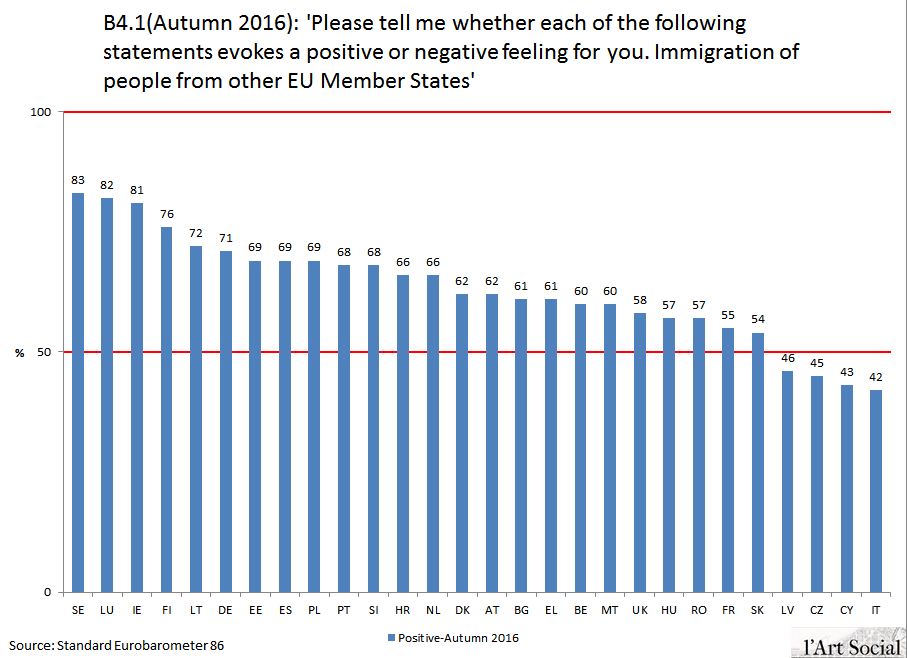

However it could be that questions posed in terms of the rights of EU citizens tend to elicit positive responses which don't necessarily reflect views on the impact of EU immigration. Chart 3 supports this view: it shows the Spring 2016 positive responses to the question on subjective feelings about immigration from other EU nations. 'Positive' majorities here are generally a bit lower than those in charts 1 and 2, and there are more countries where the positive view fails to command a majority, including the UK and Italy again but also a number of the EU accession states.

So in terms of subjective attitudes to the impact of freedom of movement (as opposed to the principle) the UK looks less distinctive, while still at the negative end of the range. Majorities in France, Belgium and Greece are notably weak: in these countries, well over a third of respondents express negative views about EU migration. This throws a different light on the apparent idiosyncrasy of the UK, where views on the principle of free movement seem to closely track subjective views on EU immigration. This is much less the case elsewhere in the EU. (More on this below.)

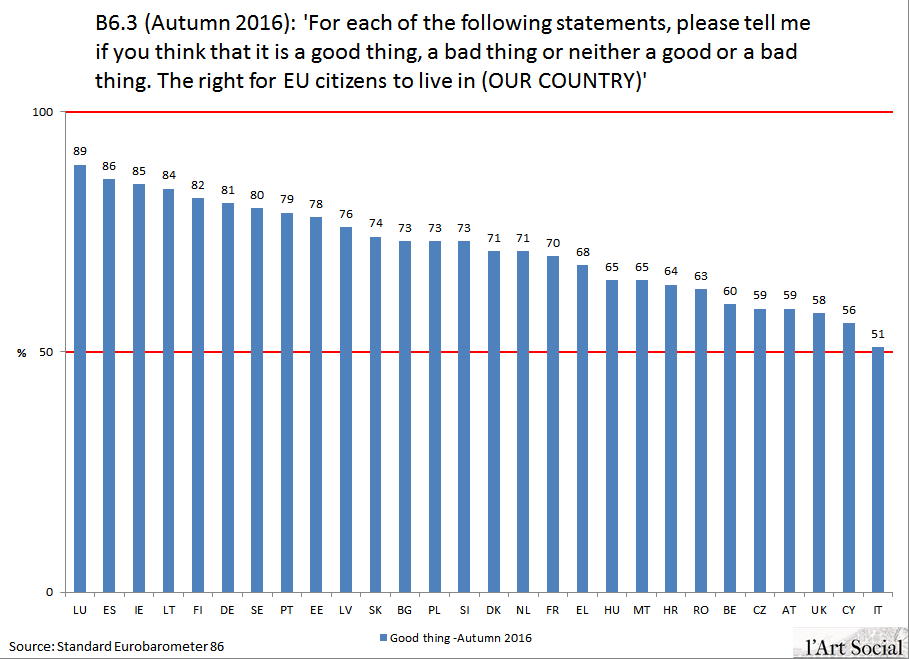

So much for the position roughly a month before the referendum. Data from the November survey shows a rather different picture. On all of the questions relating to freedom of movement/EU immigration, responses in the UK have become more, not less positive. Chart 4 updates Chart 1: 58% of UK respondents now say the right of citizens of other EU countries to live in the UK is a 'good thing', compared to 50% in May. The UK is certainly at the sceptical end of the range, but views are now similar to those in Belgium and Austria. Views on the right to work in the UK show a similar jump in support, from 57% to 64% (Chart 5). Most other countries show little (statistically significant) change, with the exception of Germany where views have also become (strongly) more positive.

The results for subjective feelings about EU immigration (Chart 4) tell a similar story, where again 58% of UK responses are positive (up from 49%), but this time views have also become more positive in a number of other countries- in fact, all the statistically significant changes registered between the two surveys are in the direction of more positive views (a reaction to the Brexit vote?) The UK is still towards the sceptical end of the range, but has moved up the ranking.

The apparent shift in UK public opinion after the referendum is something of a surprise- it certainly wasn't what I expected to find when I started looking at this data (the fact that the November results were published on December 22 may explain why they didn't attract more attention). I should imagine people will be tempted to read into this whatever their existing views suggest. In the spirit of keeping my own preferences under control, there seem to me to be two reasonable interpretations that point in different directions (but are not mutually inconsistent).

It may be that in a post-referendum climate marked by anxieties about xenophobia, racism and far-right extremism, people were less inclined to express negative views on immigration (the November survey also shows a rise in positive attitudes to non-EU immigration in the UK). The situation of existing EU migrants post-Brexit, which attracted a lot of sympathetic media attention, may also have played a role. Underlying attitudes may not have changed as much as expressed opinions, and some people who expressed support for the rights of EU citizens may have been thinking about existing residents rather than future migrants. The second point is that whatever the explanation of the shift, the idea that there is a settled anti-EU immigration or anti-freedom of movement majority in the UK, which seems to be the unshakeable foundation for virtually everything people are saying about Brexit, deserves critical scrutiny. (All these results are likley to be sensitive to the wording of the questions, on which see John Curtice here : if Eurobarometer had phrased its questions in terms of 'control of immigration' for example, the results would probably have looked very different. This point, of course, cuts both ways.)

On the question we started with- how idiosyncratic are UK views on freedom of movement?- what I've called the received wisdom needs a little modification. Negative subjective feelings on immigration from other EU nations are certainly not distinctive to the UK: France, Belgium and Greece as well as several EU accession states are among the countries where there are substantial minorities expressing discontent, or at least disgruntlement. However these attitudes do not necessarily translate into rejection of the principle of free movement, which commands strong majorities nearly everywhere. It seems plausible that in most countries, views on freedom of movement are mediated by attitudes towards EU citizenship and the 'European project' and by a sense of reciprocity (that even if there are perceived negatives to immigration, there are also benefits to being able to emigrate), rather than simply reflecting subjective feelings about the impact of EU immigration in one's own country. In the UK on the other hand these subjective feelings seem to feed more directly into attitudes towards the principle of free movement, as shown by the results from before and after the referendum. (Other interpretations are of course possible.)

The received wisdom, thus modified, seems to me to be in reasonably good shape. Those advocates of a 'soft' Brexit who hope that a general European revolt against freedom of movement will come to their rescue are going to be disappointed. Meanwhile, whatever lies behind it, the marked positive shift in UK views on freedom of movement and EU immigration deserves to be recognised in the Brexit debate. Five months after the EU referendum, nearly two thirds of UK respondents said that the right of EU citizens to work in the UK was a 'good thing'. The wording of the question and the political climate at the time of the survey may well have a lot to do with that result; that doesn't mean it should be discounted, unless we want to discount all survey responses subject to such influences- and that wouldn't leave us with much.