Causality schmausality: the employment impact of the benefit cap

As the policy was only rolled out this week, we can only ask about how people's anticipation of the cap might have affected decisions, but on the evidence offered by DWP, very few people could plausibly be held to have moved into work in response to the cap. This apparent lack of response would throw the claimed rationale for the cap into question if that rationale had any credibility in the first place. Meanwhile, people should worry less about whether the government is confusing correlation with causality and focus on how weak the causal impact of the cap on employment would be on the most generous assumptions.

Caveat: this post does not attempt to estimate the impact of the cap and the percentages I've calculated are purely illustrative. The conclusion is not that X% of people meet the basic criteria for 'moving into work in reponse to the cap'. It is that the percentage is very small on the weak evidence we have.

Have people been moving into work in anticipation of the government's benefit cap? We may never know. In order to answer that question in a robust manner the government would have had to have taken some obvious steps before introducing the policy, steps which it chose not to take. No research was undertaken into the group affected by the cap to test the basic hypothesis that the amount of benefit was acting as a work disincentive, or to see whether the households affected showed systematically different behaviour compared to otherwise similar households with lower benefit entitlements. So there is no 'pre-cap' baseline or control group against which 'post-cap' outcomes could be evaluated. It is now too late to rectify this.

But a lot turns on being able to claim that people have moved into work in anticipation of the cap. If there's no evidence for this, then the entire narrative about why a cap is needed at all would be threatened. The government wants to be able to say that the cap is resolving a problem with work incentives. If people don't respond to the threat of the cap by moving into work, we might start asking whether the issue has anything to do with incentives at all. And when people are made homeless by the cap, or forced to move from London to some cheaper part of the country, or to absorb the reduction in income in the form of reduced consumption of necessities, it is important for government to be able to say they could easily have avoided these outcomes by reacting to the incentives as others have done and getting a job. So there is a strong demand from government for anything that looks like evidence that people have been moving into work in anticipation of the cap, even though government chose not to ensure that any such evidence would be available.

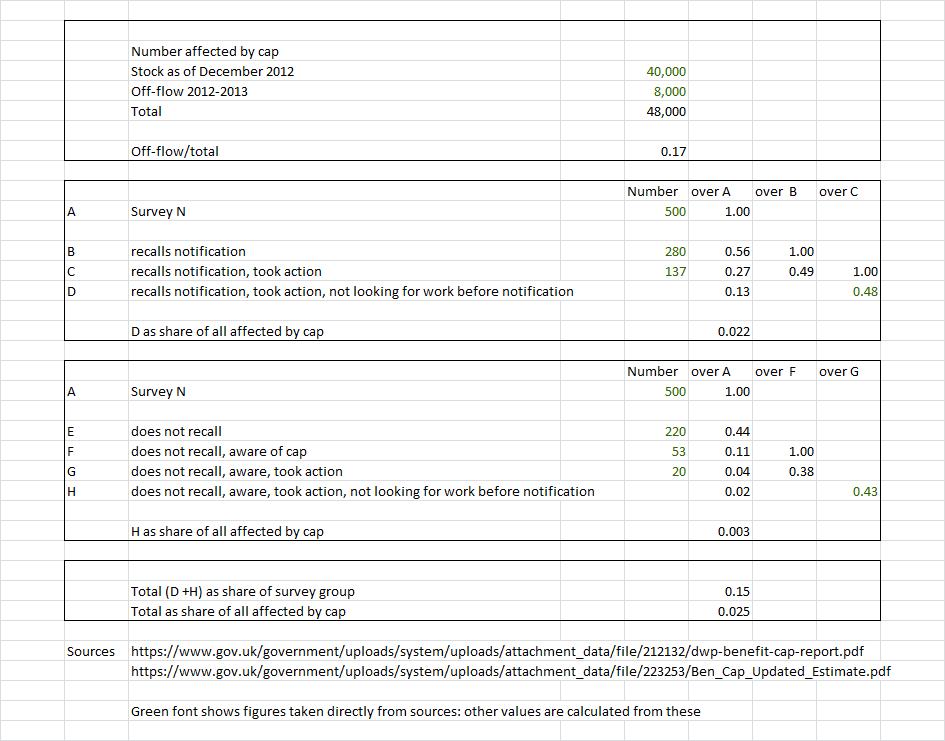

A report released by DWP on Monday https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/fil... attempted to get over the no baseline problem by asking people about how they had acted in the past in an attempt to show how behaviour had changed. There has been some criticism of this work, or rather of the way government has presented the results, a lot of it turning on the notion that ministers are confusing correlation with causality - assuming that because people looked for work after being notified about the cap, they were looking for work because of the cap. (Patrick Butler gives an excellent summary of the evidence and arguments here http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/reality-check/2013/jul/15/benfit-cap-... ) There's no question that ministers are prone to this sort of fallacy, but I think some of this criticism misses the point. Rather than asking whether the research indicates any causal impact of the cap, I'd suggest we should be asking what the maximum causal impact /could/ be, given the evidence. If it turns out that on the most generous assumptions, the impact is minimal, we don't need to worry too much about whether we are looking at a genuine causal effect or something else. The rest of this post tries to answer that question, but to cut to the chase, the maximum causal impact on this evidence is very small, in a ballpark of around two to three per cent of the people affected by the cap.

For this research Ipsos-Mori were commissioned to interview a sample of people who (a) the department had notified were likely to be affected by the cap at some point over the last year (b) who the department now believed would no longer be affected, because they had moved into employment (or for other reasons - the department's write-up is unclear on this). Respondents were asked whether they had been taken certain actions (looking for work, seeking advice etc) both before and after being notified or becoming aware of the cap.

How do we assess this evidence? I'm going to ignore the question of 'recall bias' (systematic error in recalling past events), even though this may well be a non-trivial issue in a survey which asks people to relate actions to when they became aware of something over the last year. Let's take the survey responses as a reasonably accurate account of what people did and when. If we're interested in some possible causal effect we need to define the outcome of interest and the population in question - we want a result in the form of people experiencing the outcome as a percentage of the relevant population.

The outcome of interest here is not moving into work. People move into work all the time. Rather it is a sequence: not looking for work (before becoming aware of the cap) -> becoming aware -> looking for work (after becoming aware) -> moving into work. People who have gone through this sequence are the only candidates for the outcome ‘moved into work in response to the cap’. The data in the report doesn’t quite allow us to pick out this sequence, but it gets close: for ‘looking for work after becoming aware’ we have to substitute ‘took action after becoming aware’, where the actions include looking for work, seeking advice and so on. (See questions RE4 and RE4a in the report.)

Note that the data in the report only tells us when people say things happened, not why: people were asked whether they had taken action after being notified of the cap, not whether they had taken action because they had been notified.Thus this sentence from DWP’s write-up is inaccurate: ‘Looking specifically at those who remember receiving notification or were aware that they were affected, just under half (47%) say they took some form of action /as a result/, 62% of whom say the action they took was to look for a job’.(My emphasis). Indeed, not only has the department made an unwarranted inference to causality here, it fails to mention that more than half of the 47% of respondents it is referring to were already looking for work, so the sentence is doubly incorrect.

The number meeting the criteria then needs to be assessed in terms of a relevant denominator. This would be either the total number of people who at some point over the last year were liable to be capped or, ideally, the number who were liable to be capped and became aware of this over the last year, because obviously there couldn’t be a causal impact if the claimant was unaware of the cap. The DWP report doesn’t use either of these denominators. It uses only denominators derived from the survey (possibly affected by reweighting to bring data into line with adminisitrative evidence). This of course only includes the subset of people who had moved into work . It seems obvious to me that on this ground alone, no legitimate inferences on causality could possibly be drawn from the data contained in the report: perhaps I’m missing something. However, we can give a rough estimate of an appropriate denominator based on other DWP data.

In principle we would also need a comparison group- people similar to the survey group in respects other than their benefit entitlement - in order to quantify any causal impact of the cap on employment. The impact might be overstated or understated depending on what is going on in the labour market, for example. But this doesn’t really matter in this case because the numbers meeting the criteria are so small that we won’t be looking at any potentially causal impacts in any case.

What percentage of respondents experienced the outcome of interest? By construction, everyone in the survey fits the last stage in the sequence, having moved into work (or ceased to be subject to the cap for some other reason). But of these, only 56% recalled receiving any notification (Question NO2). Of the 56% who did remember, 49% took some action after receiving notification (Question RE4), so that's 27% of those surveyed. But of that 27%, 52% were already looking for work before notification (RE4a). So about 13% of those in the survey changed their behaviour after receiving notification. Adding in people who don't remember getting a notification but were aware of the cap adds 2% to this figure. This is the candidate group for any causal impact of the cap, but the denominator is still the subset of people who moved into work.

How many people were liable to the cap over the period? The department estimated about 40,000 families would be affected by the cap as of December 2012. The number of people who have ceased to be subject to the cap over the last year is 8,000 according to DWP. Let's take 48,000 (40,000 + the off-flow of 8,000 ) as a rough estimate of the population liable to be affected by the cap over the last year. The 8,000 off-flow which is the basis for the survey group is 17% of this figure. 14% of 17% is 2.4%. This is why I say it doesn't really matter that we don’t have a comparison group, as the percentage is already too low to indicate a substantial employment impact, let alone to support causal hypotheses. A lot of people moved into work (or ceased to be subject to the cap for other reasons) over the year, but the great majority were either unaware of the cap or were already looking for work before becoming aware of it.

Note that 2.5% should be not regarded as any sort of 'estimate' of the outcome. The aim here is just to give a sense of plausible ballpark values. This is a case where saying 'very small' is more accurate than giving a percentage, and I have no wish to add to the vast number of dubious and spuriously precise welfare statistics in circulation. (If anyone is tempted to quote this piece as saying only 2.5% of people experienced the outcome, please don't.) The conclusion is that the outcome of interest, on this evidence, was only experienced by a very small minority of people affected by the cap. Or, as DWP might (incorrectly) put it, very few people have moved into work 'as a result' of becoming aware of the cap.

Some comment is needed about one of the claims made in the department's write-up of the results. The department says 'Those currently in work and who remember receiving notification that they would be affected by the Benefit Cap were asked when they received the first written notification, and how long they have had their current job. Analysis of the data shows that 61% of this sub-group found their current job after they received notification that they would be affected by the cap.... This analysis is confined to correlation and does not show causation but nonetheless among this group, those finding work after notification outnumber those who found work before it by nearly two to one (61% against 35%).

Now this is, at best, confusing- at worst, deeply confused. Forget about causality and correlation. It would be easy to read this as saying that people were twice as likely to find work after notification as before. That is not what is being said. Remember the denominator is people who are currently working, not people who received a notification. We are being told that 61% of those working found their current job after receiving notification - not that 61% who received notification are working, which is obviously not the case. Meanwhile, some 35% of people were notified /after/ they had found their current job. This is no evidence whatsoever of any impact of the cap on employment. It is evidence that the department sent a lot of notification letters to people who were already working. Why the department chose to highlight this statistic, and in such a confusing way, beats me. Perhaps someone wanted to let people know, in an esoteric fashion, just how unreliable any evidence in this area really is. If DWP can't reliably identify people affected by the cap, even the minimal outcomes identified are meaningless.

The Guardian notes: 'A DWP spokesperson accepted that while the poll did not show absolutely that the cap was having the effect intended, it did offer "quite compelling evidence".' The evidence in the report is far from compelling, and to the extent that it is evidence of anything, it is roughly the opposite of what government is claiming- the 'intended' effect is hardly materialising at all. If benefits were acting as a disincentive to work for this group, the threat of withdrawal of benefits should act as an incentive in the opposite direction, with observable impacts. If that isn't happening on a substantial scale, work disincentives may not be the issue: there may be people in this group who are unable to look for work, or unable to find work when they do look, or unable to retain work when they do find it, as well as those people who are just between jobs and fall temporarily within the purview of the cap. To me, it looks as if the balance of evidence is pointing towards most people affected falling into one of these groups. But then I'm hardly neutral on this issue http://lartsocial.org/benefitcap . No doubt there are other ways of interpreting the evidence, such as it is- perhaps we shouldn't expect a big impact on incentives until the cap is imminent, for example. But the safest conclusion might just be that all the evidence presented so far is pretty worthless. (Before anyone else points it out, I'm aware that this sounds uncomfortably close to 'kettle logic' http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kettle_logic - the evidence is worthless /and/ it's telling us the opposite of what the government is saying. I blame the weather.)

The cap was adopted with no evidence base, and no research was undertaken which would have allowed any robust evaluation of its impacts, as would normally be the case with a serious reform of the benefits system. Iain Duncan Smith's resort to faith-based assertion about the impact of the cap http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2013/jul/15/benefit-cap-editorial should be seen in this context. He has no evidence for his assertions because he did not choose to commission any, and his department's rather half-hearted attempt to patch up this omission hasn't helped. It has only reinforced the sense that government is looking for a story to tell, is indifferent as to how accurate that story is and is unconcerned about finding out what is really happening.