Deservingness, stigma and welfare (with Ben Baumberg and Kate Bell)

In his 1942 report 'Social Insurance and allied services' Beveridge set out a plan for a system of social security which would be free of the stigma associated with earlier forms of public assistance. Seventy years later, it would be hard to argue that benefit stigma has disappeared. On the contrary. outlandish slurs against benefit claimants as a group have become an accepted part of the political language, and the default setting for public attitudes is widely seen as one of suspicion and resentment, as described by one disabled claimant: ‘there’s that awful feeling that people are watching you ... even just your neighbours, because there is just this feeling of just, sort of unpleasantness’. An unemployed claimant sums up the dominant public view of people on benefits: ‘parasites, skivers, work-shy, lazy, stupid, feckless… ‘

Those quotations come from focus groups we conducted as part of the research for the report Benefits stigma in Britain http://www.turn2us.org.uk/PDF/Benefits%20stigma%20Draft%20report%20v9.pdf commissioned by the charity Elizabeth Finn Care. Our aim was to provide a map of stigma as it exists today and to understand the factors behind it. The issue of benefit stigma crosses a boundary between public attitudes, as captured in opinion polls for example, and people’s lived experience. Accordingly, the research made use of a specially commissioned opinion poll and analysis of media coverage on the one hand and focus groups with claimants and non-claimants on the other.

One of the key findings from the survey is that British people do not generally believe that claiming benefits is something that people should be ashamed of – only a small minority agree strongly when asked ‘Would you yourself be ashamed to claim benefits’ (about 10%). It is not benefit receipt itself which attracts stigma but beliefs about how ‘deserving’ claimants are- how great their need is, how responsible they are for their situation, whether they have worked in the past or will work in the future. But how do members of the public, including benefit claimants themselves, arrive at opinions about how deserving claimants are in general? It is sometimes assumed that views are a transparent expression of personal experience- as when politicians uncritically retail grievances against claimants they have heard on the doorstep. Alternatively, negative attitudes are sometimes written off as an expression of pure prejudice or ideology. Both of these approaches ignore the role that second-hand information is likely to play when people make judgements about how deserving claimants are.

To see how important secondary sources of information such as the media can be, consider this finding from our survey. We asked claimants of sickness and disability benefits how visible their conditions were in a range of social contexts- being seen in the street, meeting someone properly, knowing someone quite well and so on. Only 21% of claimants said that their condition would be obvious to someone in the street. This indicates just how thin the information available to assess deservingness can be, which will tend to make information from other sources more important.

So what sort of information about claimants do people receive from the media? Using a database of 6,600 national press articles between 1995-2011, we quantified the use of language about such aspects as ‘fraud’ or ‘need’, and the appearance of specific themes such as ‘never worked/hasn’t worked for very long time’, ‘better off on benefits’ and so on.

Perhaps the most striking finding was an extraordinarily disproportionate focus on benefit fraud: some 29% of news stories across all titles referenced fraud over the period. Bear in mind that DWP’s estimate of fraud across all benefits is 0.7%. We also looked at the sort of stories which referenced fraud: not surprisingly a large share were tabloid stories based on individual cases, but perhaps more surprisingly, a large majority originated in the Westminster policy process- stories based on statements by ministers and MP’s, select committee reports, statements from think-tanks and pressure groups and so on. If the UK media seems to have a strange obsession with benefit fraud, this reflects the obsessions of the political class.

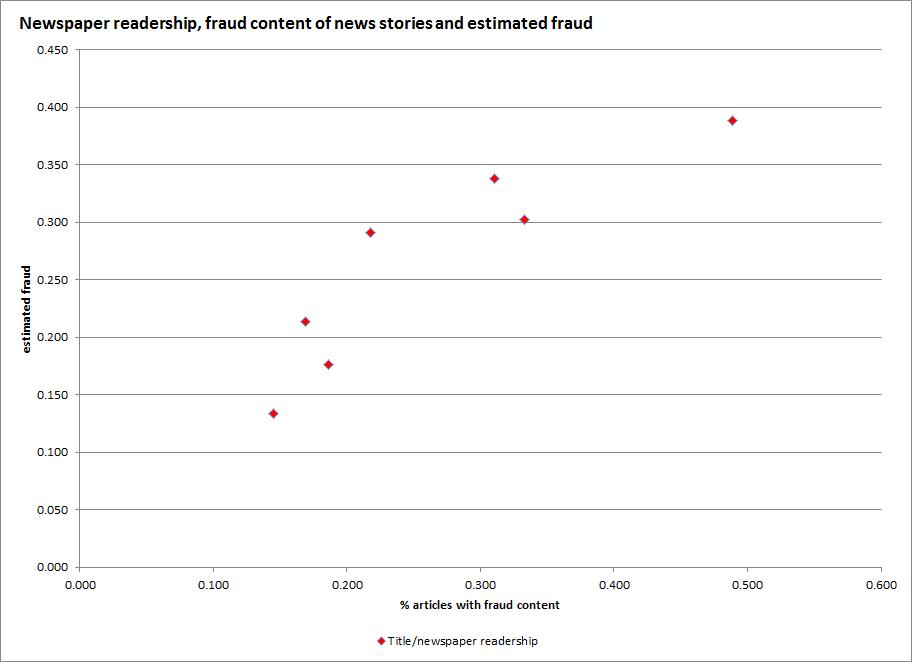

Beliefs about benefit fraud are of course only one aspect of stigma, and not necessarily the most important. But in the case of fraud, we can assess the realism of media coverage and public beliefs using robust evidence about how much fraud there actually is. Our hypothesis is that the disproportionate focus on fraud in the press affects the public’s perceptions of deservingness, because people supplement the limited information from direct experience with information derived from the media. In our survey we asked respondents to estimate how many claims were fraudulent: the question we used was designed to eliminate any possible ambiguity that what we were asking about was deliberate fraud rather than some other behaviour people disapproved of. The average estimate was 25%. It seems that the British public believes that one in four out of work claimants is committing fraud- and this seems highly consistent with the level of media coverage of benefit fraud. There is also a striking relationship between the amount of news coverage of fraud in particular titles and the estimated fraud levels among readers of those titles, illustrated in the chart.

Of course correlation is not to be confused with causality: people who are inclined to suspicion of claimants are likely to read newspapers that support their preconceptions. Note also that even the lowest estimate of fraud here (among Guardian readers) is still far higher than DWP’s estimate. Nonetheless, the relationship between newspaper readership and estimated fraud remains statistically significant even after we control for other variables associated with beliefs about fraud. The hypothesis that people fill out the incomplete information they have on the deservingness of claimants with what they are familiar with from media coverage stands up pretty well.

We also used a survey experiment to see whether thinking about fraud had any measurable impact on stigma: some of the respondents were asked to estimate fraud at the start of the interview and some at the end. The latter group’s responses to the other survey questions thus could not be affected by the fraud question. We didn’t expect to get strong results from this (this is a pretty weak experimental design), but we did find that those who were asked about fraud at the start were slightly but significantly more likely to express a sense of personal stigma. Our interpretation is that just mentioning fraud is enough to open up the question of deservingness for many people.

This brings us back to our starting point: it is /perceived/ deservingness which drives benefit stigma, and public discourse around social security in the UK seems almost to be designed to minimise perceived deservingness. This is not just about fraud, but also about other sources of ‘undeservingness’ . In fact, over recent years fraud has become less dominant in critical coverage of benefits, yielding to a language of ‘non-reciprocity’ or ‘scrounging’ (terms such as ‘handout’ ‘feckless’ ‘something for nothing’). We find similar trends in the content of articles: in more recent years (post 2003) the press has devoted somewhat less space to fraud and a lot more to people who (it is held) shouldn’t be claiming for reasons other than fraud. We also see significant increases in the use of such well-worn stigmatising themes as large families, anti-social behaviour and claimants who have never worked.

We believe the report offers strong evidence that the public discourse about welfare has an impact on the public’s beliefs about benefit claimants- including the beliefs of claimants themselves, who in our focus groups were keen to distance themselves from ‘scroungers’. And in the case of benefit fraud, the evidence suggests that it is the politics of welfare which drives disproportionate press coverage. A particularly worrying aspect is that there now seems to be a feedback loop between politics, media coverage and public attitudes: over the last three years politicians of all parties have sought to calibrate their statements to reflect what they say members of the public have told them (call it the Gillian Duffy effect). But what members of the public tell politicians is influenced by media coverage, which in turn is influenced by, amongst other things, what politicians say. (Gaffney has written about this phenomenon here http://lartsocial.org/largefamilies )

In other words, the public discourse of welfare seems to be caught in a vicious circle. That was an eventuality Beveridge never anticipated when he set out his plan for a stigma-free social security system.

Sources for chart : Mori survey for Elizabeth Finn Care report; 20% sample of articles in media database for Elizabeth Finn Care report

This is a longer version of an article which originally appeared on the New Statesman's Current Account economics blog http://www.newstatesman.com/economics/2012/11/scroungers-fraudsters-and-... Thanks to Alex Hern for commissioning the original piece.